In Part 1, we discussed two events that simultaneously occurred and changed baseball for over a decade. Pitchers started throwing significantly faster and hitters started the launch-angle revolution. We also outlined three different kinds of hitting zones: the “strike” zone, the “contact” zone, and the “power” zone.

In Part 2, we will build upon how pitching strategy has changed, utilizing analysis of each zone to fully grasp that metamorphosis.

CHAPTER III: Coming Together

Pitchers in the pre-DIPS era pitched differently; they would exploit the differences between zones to achieve success and pitch effectively. While the byproduct of pitching well still led to the same DIPS results (high strikeout rates, low walk rates, and low home run rates), the process was almost completely different. While a goal of any pitcher is to throw strikes which appear to be balls and balls which appear to be strikes, pre-DIPS era pitchers used a different playbook in terms of pitch sequencing and command.

The exploitation of hitters’ zones meant pitching within the areas of the strike zone that a hitter couldn’t cover. In other words, they were avoiding a hitter’s “contact” zone while still throwing strikes. Therefore, they would not only manipulate what was and wasn’t a strike to their benefit but also manipulate what was and wasn’t a strike in and out of a hitter’s “contact” zone.

Historically, this trend is what led to pitchers achieving success and what has drastically changed since the launch-angle era. The launch-angle era turned the low fastball (especially low and-away), a cornerstone of pitching horizontally, into a home run and brought an end to pitching horizontally. The Greg Maddux method of pitching utilized the low corners of the strike zone as his targets, for which he’d throw his fastball, then tunnel his changeup and slider off the fastball. This meant hitters swinging and missing at pitches they expected in the strike zone while taking pitches that were outside of it.

Yet, Maddux was never considered a strikeout pitcher. Instead, he forged his identity as a low-pitch count pitcher who threw a ton of innings. His sui generis ability to throw complete games while throwing fewer than 100 pitches led to the formation of a new expression throughout the game of baseball. That feat is now known as a “Maddux” in homage to the Hall of Famer’s unique ability. Maddux was able to limit his pitches while racking up innings as opposed to strikeouts. He exceeded 200 strikeouts only once in his entire career, but he threw 220-plus innings 12 times.

Maddux’s style of pitching is paradigmatic of pitching horizontally. He didn’t tally strikeouts, instead attacking the areas of the strike zone that hitters had trouble with. This led to weak contact as batters were often baffled by the array of fastballs, sliders, and changeups on and off the lower corners of the plate.

This style of pitching completely changed during the launch-angle era as hitters stopped caring about striking out. They stopped having two-strike approaches or choking up on the bat and instead aimed at expanding their “power” zone as much as possible. This ultimately cost them a great deal of their “contact” zone in the process. The launch-angle approach led to the death of horizontal pitching as the low and away fastball became fodder for the home run. Yet, eventually, the continuous expansion of their “power” zones caught up to the launch-angle practitioners (Cody Bellinger, Joey Gallo, and Christian Yelich, for example). These players had unwittingly sold out a more robust “contact” zone for more home run power.

While the home run is the best play in baseball, hitting a single is significantly easier. Historically, a player has had 240 hits or more 15 times, and some of those came in 154-game seasons. That equates to an average of three hits every two games. Meanwhile, the most prolific home run demonstrations (at least 60 in one year) have only occurred nine times all-time, or a little over one home run every three games.

The reason I cherrypicked these figures is not only because they are round milestone numbers or because they have been considered rare feats accomplished in the history of the MLB, now spanning three millennia. It’s because the figures provide symbolic verisimilitude. 240 singles and 60 home runs share the same amount of total bases. This study is wholly anecdotal as the 240 hits were not all singles and the 60 home runs were not the only hits produced. So, for those interested in something a bit more practical, the run value of a single in 2023 was .88 runs and that of a home run was two runs. Therefore, about 2.27 singles equates to the value of a home run, significantly less than the total bases value of four.

CHAPTER IV: The 2023 Season

This past season, the pendulum has started to creep back toward a more well-rounded offensive approach, one which does not impede a hitter’s ability to make contact. This is due to a myriad of reasons. First and foremost, the game has started to shift toward younger, more athletic players. These players are not only faster but also not as mature hitters. Therefore, a trend of small ball (hitting singles, bunting, and stealing bases) has come back into vogue. Secondly, recent rule changes such as the pitch clock, throw-over limit, and ban on shifts make playing fast. As a result, hitting to all fields and running the bases at a high level become much more crucial.

The launch-angle era took off, both literally and figuratively, during a time in which low fastballs were commonplace and breaking pitches were thrown mainly to strike hitters out. The pendulum swung completely in the opposite direction as pitchers threw their fastballs predominantly up in the zone while seldom throwing fastballs in hitters’ counts. Pitching backward became a new norm, using breaking and offspeed pitches to get ahead in the count while countering with a fastball up in the zone to put hitters away via the strikeout. Combined with everyone throwing 95 mph or faster, this made it way more difficult for launch-angle specialists to hit home runs.

Since hitters were being pitched in areas of the plate where they struggled to even make contact, this trend not only tanked their power but also their batting average. Hitters who had hit .240 to .260 with 30 to 40 home runs suddenly found themselves hitting below .200 with just 15 to 20 home runs. In other words, All-Stars were turned into fringe major league players.

Not to be overlooked is the change to the baseball that occurred before the 2021 season, as well as the league mandate for all teams to store their balls in a humidor. The ball that had been used for a few seasons in the late 2010s was supposedly bouncier and produced absurd home run numbers. A return to the classic ball helped keep home runs more in line with where they had always been.

Entering 2023, no one knew how the rash of young players and prospects entering the league would mesh with the new rule changes. We were met with a few surprises, including the lightning-quick turnarounds of young teams like the Orioles, who won 101 games, the Reds, and the National League champion Diamondbacks. Yet, no one could have foreseen how the Orioles and Diamondbacks, who made few (if any) personnel moves to their rotations, would experience significant improvements from their starters.

What I believe to be attributable to their progressions is a return to horizontal pitching. Now that hitting approaches around the league have started to change, pitching low in the strike zone is on the rise. Creating weak contact and ground balls is the new old trend and the importance of a sinker is coming back.

The sinker or two-seam fastball is a pitch with two-plane movement. In other words, it moves both laterally and downward. Depending on grip, arm angle, and other factors, each pitcher’s two-seam fastball is unique in its movement, possessing either more lateral or downward movement. The two-seam fastball is also incomparable in that it has significantly more movement than a four-seam fastball, yet it has much more velocity than breaking and offspeed pitches. The benefit of having high velocity and movement? The fastball is easier to locate than slower, heavier-moving pitches.

The sinker is the perfect pitch to throw both as a ball that looks like a strike and a strike that appears to be a ball. For example, in an all-right-handed matchup, the pitcher can throw sinkers low and in for strikes and then get the batter to fish for that very same pitch below the zone given its parallel trajectory. At the same time, the pitcher can either start the count or end the at-bat with a backdoor sinker which starts off the plate and then “comes back” over the outside part of the zone for a called strike. This is the versatility of the sinker.

Furthermore, both the slider and changeup play off the sinker very well because all three have overlapping two-plane movement on the x- and y-axis. This makes tunneling all three pitches seamless and can create serious problems for batters who not only have to deal with all the movement but also disruptions in their timing. The only issue with the sinker is that it is mainly effective at or close to the horizontal borders of the strike zone and is generally thrown down in the zone.

The goal of the sinker is not only to trigger confusion but also to induce weak contact by missing the barrel of the bat. This idea was upended by the launch-angle revolution due to two factors. The first is their location; sinkers are mainly thrown low in the zone, and these launch angle sluggers hunted them. Low strikes, especially hard ones like a sinker, were their bread-and-butter and they exacted lots of damage on any low pitch in general. Secondly, the trajectory of the sinker as a two-plane pitch made it easier to lift, as the pitch runs directly into the swing path of same-handed hitters.

A key difference in launch angle approaches, which also epitomizes the movement toward pitching vertically as opposed to horizontally, is its method of creating power. Until the dawn of the launch-angle era, hitters would mainly generate power by extending their arms. Therefore, hitters could turn pitches up or out over the plate into homers. During the launch-angle era, hitters used the angle of their swing to generate power, which in turn made arm extension obsolete. It also opened up that previously dangerous area of up and out over the plate into an area of exploitation for pitchers, especially against launch-angle hitters.

Therefore, sinker usage epitomizes the movement of the game from horizontal to vertical pitching and now, once more, back to horizontal pitching.

In Part 3, we will tackle the movement of pitches as they affect the way hitters make contact, as well as the real impact DIPS theory had on the game of baseball.

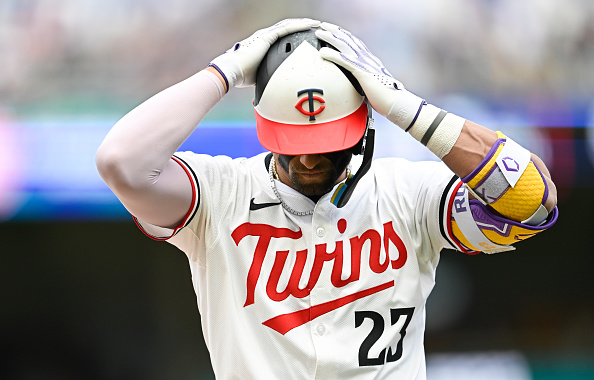

Main Image Credit: