Beth Sullivan | November 8th, 2018

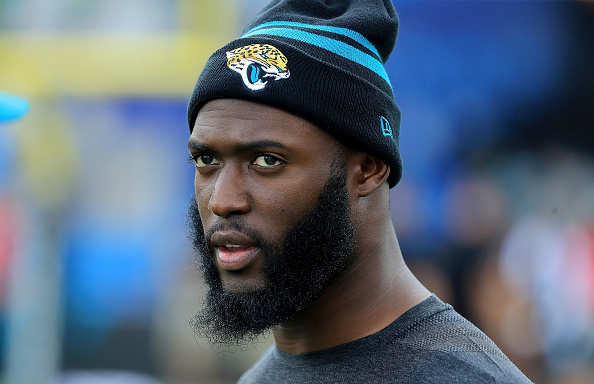

Matt Bryant – Atlanta Falcons Kicker, Charles Clay – Buffalo Bills Tight End, Leonard Fournette – Jacksonville Jaguars Running Back lead a long list of NFL players who are or have battled hamstring issues during their career. Some players return after a week or two and some end up on IR. What makes hamstrings so difficult to pinpoint a time to return to play?

Hamstring injuries are the 2nd most common injury in the NFL each season. Each team experiences an average of 6-7 injuries each season and reinjury occurs more often than the initial injury. Reinjury was the case with Fournette who first went down during the season opener and then has been down since retweaking in week 4.

Hamstring injuries are common in athletes who have to accelerate, decelerate rapidly or just do a lot of running. This means that in the NFL DBs, WRs, RBs, running QBs, and to a lesser degree, kickers are the most commonly bothered by this ailment. Kickers tend to suffer from Low Stretch injuries. More on these type injuries below. The hamstrings are a group of muscles that run down the back of the leg from the pelvis to the posterior lower leg along the tibia and fibula. They are responsible for fully flexing the knee.

The 3 muscles that make up the hamstring group from inner leg to outer leg are the semimembranosus and semitendinosus muscles, which attach to the inner lower leg along the tibia after passing thru the knee and the biceps femoris muscle which attaches to the outer fibula.

Hamstring injuries are characterized by sudden shooting pains in the back of the leg. While the injury can occur anywhere along the muscle, they most commonly occur in the middle of the muscle where the tendon and muscle interact. Generally, the pain makes straightening the leg fully impossible. In other words, the leg is unable to extend without pain. Hamstring injuries are graded according to severity and associated symptoms.

Mild (Grade 1) Injury

- Stiffness, tightness and mild tenderness to palpation along muscle bundles in back of the thigh

- No noticeable swelling at rest

- The heel is raised by flexing the knee

- Gait is normal without a deficit in the range of motion.

- Mild discomfort only while walking

- Usual recovery time 2-3 weeks

Moderate (Grade 2) Injury

- Gait noticeably affected. Limp when trying to ambulate due to pain with knee extension

- Tightness with significant twinges upon flexing the knee

- Palpable muscle tightness in the back of the thigh

- The range of motion is limited and marked pain when flexing the knee

- Pain generally relieved or tolerable when no weight on the affected leg

- Usual recovery time 4-6 weeks

Severe (Grade 3) Injury

- Posterior thigh swelling and bruising which is markedly tender even to light touch. Occasionally hematoma develops which forms firm lumpy texture to posterior thigh. This is related to the nature of the deep bruising associated with this degree of injury.

- Significant pain at rest which becomes markedly more severe with any ambulation

- Ambulation is difficult without assistance either through another person or device

- Usual recovery time Greater than 8 weeks

Recovery and Reinjury

In an MRI study done in 2014, despite being pain-free after an average of 15 days, evidence of sustained injury still was evident on MRIs which were done at the six-week post-injury point in over 50% of the athletes examined. The athletes used in this study had been diagnosed with a grade 1 or 2 strain initially.

What exactly does this mean? If the injury is still evident at six weeks on the MRI, it means that full healing has not taken place and the risk for re-injury is still significant. This is what happened with Fournette, who returned and played in part of game 4 and has not played since. Even though he is scheduled to return to the field this week, there is still a risk of reinjury.

In addition Grade 2 and 3 injuries involve actual tears of the muscle which results in the formation of scar tissue that markedly changes the consistency and function of the originally injured muscle as well as interferes with the function and use of the muscles around the injured ones.

A number of treatment options have been tried to speed the recovery process including deep ultrasound therapy, cryotherapy, and platelet-rich plasma. Results have been mixed and currently, no one treatment option other than adequate healing time has been shown to decrease the rate of re-injury.

Another interesting study has found that the injuries that have the longest time to heal are the ones classified as low stretch injuries. These occur during stretching type exercises and activities and result from extensive stretching of the muscles. While they don’t appear as bad initially, they actually cause more extensive deep injury to the muscles and the risk for re-injury is almost 3x that of injuries that occur during active movement like high-speed running. This is the type of injury to the hamstring usually sustained by kickers.

Professional sports is a business, and getting athletes back on the field quickly is important. However, if the risk of re-injury is so great, is that really the best thing in the long run? Until a way to limit and treat hamstring injuries is found, adequate healing time is imperative for the athlete’s health and long-term playing future. These findings are one of the reasons more and more athletes with significant hamstring injuries find themselves on injured reserve much faster than they previously did.

Questions and comments?

thescorecrowsports@gmail.com

Follow Us on Twitter @thescorecrow

Follow Us on Reddit at u/TheScorecrow

Follow Beth Sullivan on Twitter @GAPeachPolymer

Main Credit Image: [getty src=”1035003754″ width=”594″ height=”384″ tld=”com”]